Japan’s data center (DC) market is experiencing rapid growth and has increasingly become an attractive investment target for both domestic and overseas investors. Globally, merger and acquisition activity in the DC sector hit record levels in 2024, and this trend is expected to continue through 2025 and beyond.[1]

Japan is the second-largest DC market in Asia and the third largest globally behind only the US and China. The country is well-positioned for continued growth for DC investments, due to a combination of factors including a robust and stable infrastructure foundation, advanced technology (especially artificial intelligence) and IT landscape, strategic location, reliable power supply and a favorable regulatory environment, together with strong Japanese government support for such initiatives. The Japan DC market is seeing a wave of hyperscale developments, particularly in metropolitan hubs such as Greater Tokyo and Osaka.

This market update discusses recent DC transactions in Japan, key legal developments affecting DC projects and the common structures used for Japanese DC investments.

- Latest DC deals and opportunities

There is strong momentum for DC investments across the country, with major Japanese and international players announcing large-scale investments into DC projects. Some of the latest DC deals in Japan include:

- October 2023 - SoftBank and its subsidiary IDC Frontier’s $420 million DC development in Hokkaido, partially subsidized by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.

- February 2024 - CapitaLand Investment Limited’s acquisition of land in Osaka to develop its first DC in Japan, entailing an over $700 million investment.

- December 2024 – US investment company Asia Pacific Land’s $2 billion investment into multiple DC projects in Fukuoka Prefecture, with construction scheduled to begin this year.

- March 2025 – Mitsui & Co.'s acquisition of a 50% stake and 18 billion yen investment in a hyperscale DC project in Kanagawa Prefecture, alongside institutional investors from both Japan and overseas.

In recent years, Japan has witnessed the development of several self-build hyperscale DC facilities by leading US tech platforms like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon. In January 2024, Amazon Web Services announced plans to invest a further $15.5 billion to expand its DC portfolio in Japan, building on its initial entry into the market in 2011. Microsoft, which launched its first two DCs in Tokyo and Osaka in 2014, also announced last year that it would invest an additional $2.9 billion to expand its DC capacity in Japan over the coming year.

- Legal and regulatory developments

Data protection

The Act on the Protection of Personal Information Protection (the APPI)[2] is currently Japan’s only comprehensive data protection regulation applicable to DCs. This makes the country an attractive destination for foreign entities to host data. Globally, evolving data localization and sovereignty rules are increasingly influencing where users choose to procure DC capacity. For example, countries like the US and China have recently introduced stricter laws requiring certain types of sensitive data to be stored locally. Japan, on the other hand, currently has no specific data localization requirements nor broad provisions for government access applicable to DCs generally (although this may change in the future), which can be seen as an advantage for foreign operators using DCs in Japan. Moreover, Japan’s data adequacy status from both the EU and UK[3] allows for the free flow of personal data from these regions to Japan without the need for additional safeguards, simplifying cross-border data transfers between these jurisdictions.

ESG concerns

DC facilities consume a substantial amount of energy and resources, and such needs will only continue to increase as the demands for data storage and usage expand to meet the needs of the market and technology. Japan’s Act on Rationalizing Energy Use, which was first introduced in 1973 and most recently revised in May 2022 in response to Japan’s goal of carbon neutrality by 2050[4], seeks to curb overall energy consumption by businesses. DC facilities that fall within the regulation’s scope are subject to a benchmarking system and the DC operator (whether the building owner and/or leaser of a building[5]) must submit annual reports in connection with their energy usage and related data of their respective DC operation.[6]

- Typical DC investment structure in Japan

There are two structures commonly used in Japan for DC transactions and private real estate generally:

(a) the gōdō kaisha (GK)-tokumei kumiai (TK) structure, which comprises of investors acting as “silent partners” in the GK, which then acts as a special purpose company (SPC) to hold the trust beneficiary interest in the subject; and

(b) the tokutei mokuteki kaisha (TMK) structure[7], which involves the creation of an investment vehicle to acquire a particular real estate (such as a DC), as further discussed below.

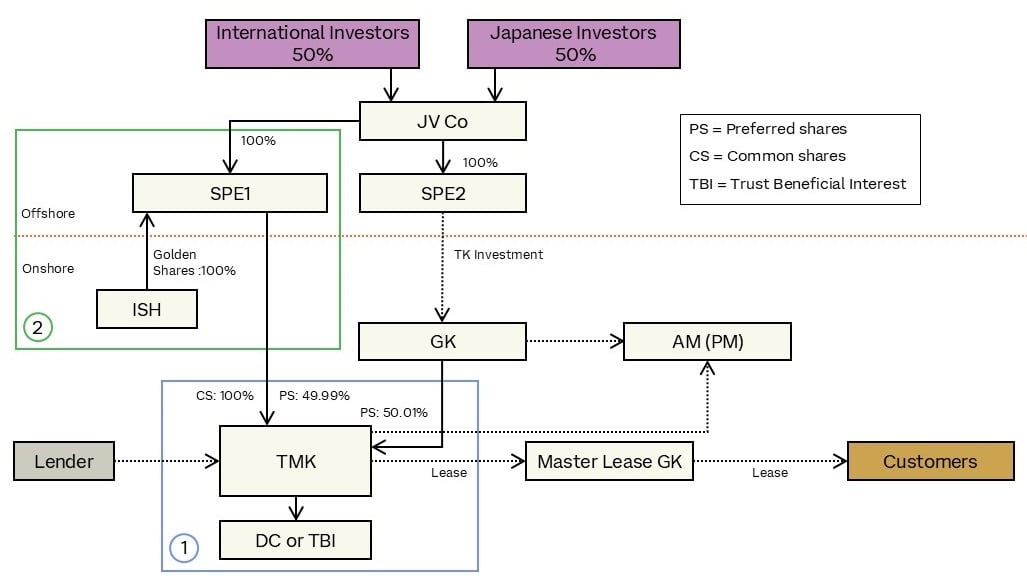

The following is a common structure used for investments in Japanese DCs:

TMK Structure

In this update, we will focus on the TMK structure, as demarcated in blue in the structure chart above, which is the most common investment vehicle for DC investments in Japan among overseas investors. A TMK structure has many similarities to other types of corporate structures, but with a unique future being that it is a highly regulated entity, which creates certain administrative (but manageable) burdens such as requirements to file an Asset Liquidation Plan with a regulator before commencing its business or entering into contracts. Nevertheless, there are a few key reasons for an overseas investor to prefer using a TMK structure over the GK-TK structure when investing in DCs in Japan, including:

(a) favorable tax treatment - subject to fulfilling certain requirements, any dividends paid by a TMK on its preferred shares will be included in its losses for tax purposes, resulting in a pay-through tax treatment (i.e., avoidance of double taxation treatment). The TMK structure also provides clearer tax guidelines and regulations generally; and

(b) fewer control issues - unlike with the GK-TK structure, where the operations are handled by at the GK level and investors do not participate in or control management, investors in a TMK can, by way of both equity and contract, control the management and general corporate affairs of the TMK.

A TMK has two types of shares:

(a) common shares (sometimes known as “specified” shares), which are voting shares to control the TMK; the common shareholders (or “specified” shareholders) have voting rights at the shareholders meetings; and

(b) preferred shares, which are typically non-voting shares with rights to preferred dividends and preferred distribution of the residual assets (i.e., carrying economic but not governance rights)[8].

In order for the TMK to enjoy the pay-through tax benefit in Japan, more than 50% of the common and preferred shares are required to be held by an onshore (i.e., Japanese) entity. However, the common shares may be exempt from this requirement if the common shareholders waive their right to receive dividends and residual assets under the Asset Liquidation Plan (i.e., the overview of the management and financing structure of a particular TMK as filed with the applicable Local Finance Bureau). Assuming this arrangement is reflected in the Asset Liquidation Plan, the common shares may then be held entirely by an offshore entity.

To avoid real estate acquisition tax, the DC (or other applicable real estate property) is often entrusted with a trust bank to act as trustee (i.e., a trust bank holds a title to a property on behalf of a TMK). This arrangement is referred to as a trust beneficial interest.

Use of an ISH

For DC projects involving a TMK, it is common for a general incorporated association (ippan shadan hōjin) (ISH), as demarcated in green in the structure chart above, which is solely controlled by a neutral third party (such as an independent accountant) to either be: (a) a sole common shareholder of the TMK or (b) the “golden shareholder” (ISH in the above chart) of the TMK’s sole common shareholder (SPE1 in the above chart) who holds veto rights over certain material matters and/or shareholder resolutions of SPE1 (e.g., disposal of the DC that is held by the TMK). This governance structure is often required by lenders to ensure bankruptcy remoteness, which is essential in order for the TMK to qualify as a pass-through entity (i.e., to issue specified bonds to qualified lenders).

There are also tax treaty considerations. For example, to benefit from the Japan-Singapore double taxation agreement, which allows for a reduced 5% withholding tax (compared to the standard 20.42% withholding tax in Japan), at least 25% of the TMK’s common shares must be held by a Singaporean entity – this is the rationale for using option (b) over option (a) in the preceding paragraph in such circumstances.

License requirements

Having title to network facilities and servers could require a license under Japan’s Telecommunications Business Act. The Telecommunications Business Act regulates the telecommunications business and, if certain conditions are met, requires a company to register or file a notification prior to commencing business operations. As such, such DC project could avoid triggering this license requirement depending on the scope of services provided by the SPC vis-à-vis the other constituents of a DC project.

In both the “leasing” model and “outsourcing” model described below and as illustrated in the structure chart above with respect to the TMK structure, the “Master Lease GK” leases the relevant DC building (core and share) from a TMK (or, if applicable, a trust bank) and develops a building with a stable power supply, earthquake-proof facilities and other basic requirements to satisfy building and safety regulations. In order to avoid triggering the license and regulations pursuant to the Telecommunications Business Act, in such arrangement the Master Lease GK is only providing the physical space, air conditioning and power supply but not the network facilities and the servers that are placed inside the building. The Master Lease GK then either: (i) rents out the space to a telecommunications carrier who (or allows end users to) install their own network facilities and servers in the building (known as a “leasing” model) or (ii) rents out the space to end users and enters into a management agreement with a licensed telecommunications carrier who (or allows end users to) install their own network facilities and servers, and operate and manage the DC (known as an “outsourcing” model). With the help of a Japanese JV partner, in some cases a JV company may establish a new management company that obtains a telecommunications carrier license to operate the DC directly.

[1] https://www.srgresearch.com/articles/its-official-data-center-ma-deals-broke-all-records-in-2024

[2] https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/en/laws/vie

w/4241/en (English translation of the APPI, as provided by the Japanese Ministry of Justice)

[3] https://commission.europa.eu/law/law-topic/data-protection/international-dimension-data-protection/adequacy-decisions_en (for the EU) and https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-japan-data-adequacy-joint-statement/uk-japan-data-adequacy-joint-statement (for the UK); these are subject to certain supplementary rules enacted by the Personal Information Protection Commission: https://www.ppc.go.jp/files/pdf/Supplementary_Rules.pdf (in Japanese)

[4] https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/category/saving_and_

new/saving/enterprise/overview/amendment/ (in Japanese)

[5] https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/category/saving_and_

new/saving/enterprise/factory/support-tools/data/2023_01benchmark.pdf (in Japanese)

[6] https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/category/saving_and_

new/saving/enterprise/factory/faq/pdf/a1-18.pdf (in Japanese)

[7] The introduction of the new lease accounting standards in 2027 may create discrepancies between TMK's Japanese generally accepted accounting principles and tax treatment of lease payments. To mitigate the complexities and potential tax inefficiencies, setting up a lower TK-GK structure, whereby the TMK acts as the TK investor and GK acts as TK operator holding a TBI representing a DC, is currently under discussion among practitioners.

[8] Please note that a TMK is not permitted to issue golden shares.